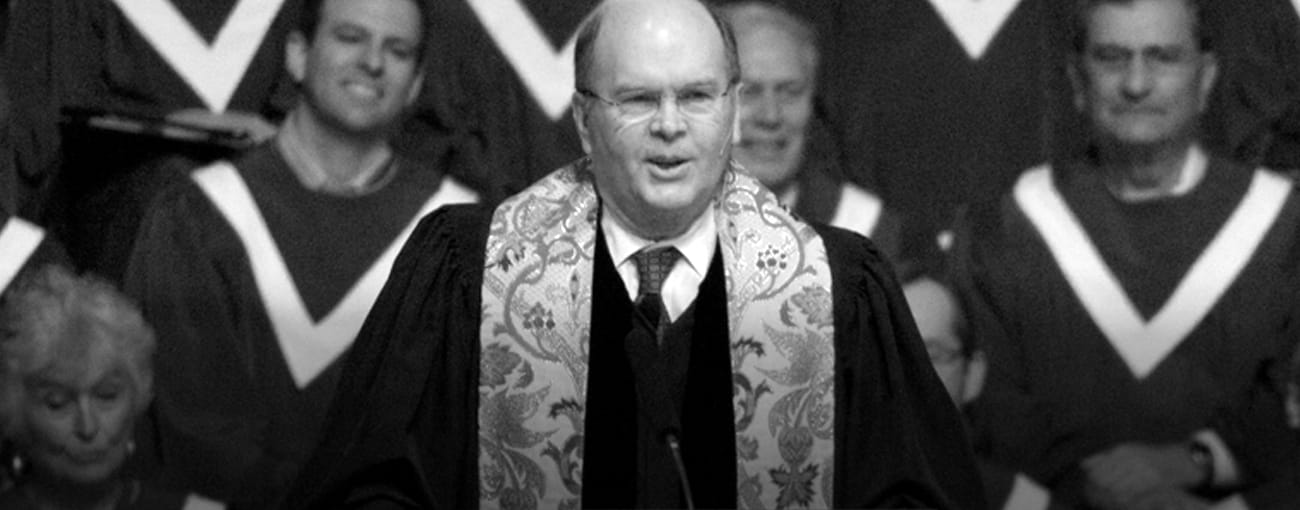

An Interview with Mark Craig

The capstone of the Reverend Mark Craig’s 41-year career was his leadership of Highland Park United Methodist Church, where he was Senior Minister for 18 years from 1995 to 2013. The Church’s congregation comprises multi-generation families and individuals who are significant civic forces. President George W. Bush has been quoted as saying that one of Mark Craig’s sermons was part of his inspiration to run for President. Craig has also been a friend and mentor to members of the Tolleson Family.

As part of the Family Education series, Carter Tolleson sought Craig’s wisdom regarding parenting, the impact of wealth on family dynamics, and other matters in the complex interplay of behavior in families. Their conversation follows. Some responses have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Carter Tolleson: I’m interested in your family, what your background was like.

Mark Craig: There were five kids in my family; I was in the middle by birth order, grew up on the west side of Fort Worth. My father was a business man and pretty much turned over the parenting to my mom. That was the model I understood. But deep down, I knew I wanted more if I ever had children—a closer relationship [with my children]. I didn’t want to be better than my father; I wanted to be different from my father. I wanted to structure my vocational day so that I could be different for my children. And I did; I think it was really helpful. My father had five children; he was busy making a living.

CT: Clearly family life and upbringing shape a lot of who you are. What led you to the path to seminary?

MC: I grew up in a church family. I went to seminary to explore something in my own life. It was at Duke, in my second year, that I felt called to serve God. It was the opposite of an intellectual pull—it was transcendent. It led me to examine life in a different way, a less intellectual way. I had a sense of lostness, a yearning. I wasn’t desperate. I just felt that life was slipping away [if I didn’t do something]. And it wasn’t immediate; it was about ten years before I realized “this is the right thing for me.”

CT: Not everyone is as lucky as you – to feel a transcendent calling for something. There are a lot of people trying to find their purpose in life, especially as kids and young adults. Do you think it’s unusual for young people to be actively searching for their role in life?

MC: Not unusual, maybe, but it’s probably unusual for them to articulate it with parents, family, others. They don’t know how to articulate it, don’t know how to address it. They don’t know how to move forward.

CT: Our recent Family Education Speaker, Adam Braun, says in his book, “the single most powerful element of youth is that you don’t have the life experiences to know what can’t be done.” So, in a way, the search for purpose as a youth can be a powerful thing. How do you advise people who are seeking their way, their calling, or purpose in life?

MC: We talk about hopes, desires, dreams in life, how to do things. I try to talk to people about what’s getting in their way. I often find that people are doing things that are the expectations of others, and deep down, they are angry; they’re unhappy. But frankly, for many people, money is a barrier. It just takes too much money for them to live the way they want to live. There is an expectation that you have to have a whole lot of things to be happy.

CT: I agree that money can be a barrier for achievement. It can also be the greatest cause of family disputes. Since you brought it up, I’ll ask the question. We deal with it in our business, we deal with it with our families; what are your thoughts on keeping up with the Joneses? How does having money impact a family?

MC: My experience on that is a little different. As the minister of a church, I was able to say to my children that “we don’t need some things that others have.” My role put me in a special place. My children didn’t put any pressure on me to have more things. But I did talk with families whose children put pressure on their parents to produce because they would see the things that others have. You know when I was growing up I remember my father having a particularly tough year—he was in the oil and gas business, and times were tough. We didn’t have much, but everybody pitched in. It was the best Christmas we ever had. But money is a pressure in the other direction, too. People who pretend [to their children] that they don’t have money always fail. They look like phonies to their kids. Others tell their children that they’ll never have to work—and you see those children without a direction, at age, say, 27. It’s hard to be a successful parent in that situation. The successful parents I’ve seen acknowledge their wealth, tell their children about it, tell them it’s not going to come to them on a silver platter and, if they have a trust, tell them they won’t realize those trusts until they’ve done something on their own. But I think that’s really hard to do—I don’t see a lot of successful stories. I see a lot of kids who look around them and want what others have, but they can’t have it. So a big parenting issue is teaching a child that self-worth is not based on what someone else has. Building a secure environment around a child is the place to start.

CT: I said in a previous Journal that your kids know you’re rich – and your grandkids know too. They are smart and perceptive. More than we give them credit for. For me, effective communication and openness can get you a long way. But in a wealthy family, how do you raise independent children? “Give them enough to do anything but not enough to do nothing?” How do you draw the line between helping your kids and enabling your kids?

MC: We [Craig and his wife, Sandra] told the kids the grounds rules and tried to be consistent—we set expectations. What they could have—and at what level—and what they couldn’t. But I found in my work that people find it harder to talk about money than about sex. People don’t tell their children about money. They don’t want to talk about what they made, what they didn’t make, what their budget is. A lot of the problem with money is communication. I think it’s about power and control sometimes. In my work, I saw kids who were outspending their parents’ capacity pretty rapidly. The families didn’t talk about what was possible and what their children should expect.

CT: If you take money out of the equation, does the problem go away?

MC: No; money is not the evil here, but it creates some barriers. Money enables people to live wonderful lives, do wonderful things. I’ve always felt that the best people I know are the most generous people I know. When I see these people, I find happy people, loving people, caring people. Teaching your children to be generous with the money they have is really important.

CT: I read somewhere that wealth should not be regarded as a reflection of your ego; instead it’s a tool that allows you the freedom to pursue your passion or, in some cases, gives you fame which can give you the ability to influence others, speak for those who cannot speak for themselves. What are your thoughts on that?

MC: I’ve talked to a lot of men who used money as a way to keep score on how successful they were in their lives. Without it, they can’t keep score on their success. There’s a problem with that—the net worth becomes the prize. People can become stingy and not share it with others, including family. They just want it to mount up. It’s a way of proving self-worth in an odd sort of way.

CT: How would you measure someone’s worth?

MC: Kindness and caring and altruism—the kind of characteristics of a virtuous life.

The older you get the more you realize that the people you really love are the people whose values you admire. They’re the people you admire for who they are. If you can be that for someone else, that’s pretty special. When people love you and want to be around you, I think that’s real close to immortality. It’s the influence you leave behind. That’s why when I was 55, I adopted a child. There was a part of me that wanted a second chance [The Craigs have two sons in their 30s.]. And now I have a 14-year-old daughter, and there are still some things I would want to try over. If I could do it a third time, I would.

CT: What have you done differently as a father with your youngest child that maybe you didn’t do with the older two boys?

MC: One size doesn’t fit all. I always run a business or a church with one model. If the model worked, I replicated it. I tried to do the same with my children, but I should have treated my two sons differently. Each of my children is different. You have to do what fits each child. Every child has his or her own path. And you really have to spend some time getting to know your child; I don’t think I did that as well early on. Now I drive my daughter all over [to school, lessons]. We have a lot of time in the car. I used to talk to her – my agenda – but now I let the conversation go where she wants it to go. Being in a car can be a really positive thing. It gives us so much to talk about. It gets me back to the idea of family vacations, being on the road, being in a car. Road trips with your child – that’s the most important thing you can do. Not with their brothers and sisters, but each child alone. That idea of “quality time” with a child is bogus. Time is time is time. You make something happen in that time with your child. I know some parents pepper their child with questions. Sometimes my daughter and I go in silence. Twenty minutes of silence is a good time with my daughter. Any time with my daughter is a good time. Sometimes we think silence is not being a good parent. I’m not sure that’s right.

CT: Kids can learn a tremendous amount from your past experiences; possibly avoid some unnecessary pain in their lives. But it clearly doesn’t eliminate the chance of failure, which in many cases, failure is a good thing. What experiences from your own life have you shared with your children?

MC: My willingness to share with my children my weaknesses, vulnerabilities, failures. Someone once told me that that you may see your father as a great man, your mother as a great woman, but they don’t see themselves that way. My father did not share vulnerabilities. I do, and my children know to get help when and where they need it. I think sometimes parents think their vulnerabilities will scare children. Children can accept more than their mothers and fathers accept. That’s why you share a lot of things with your children. In fact that raises a good question—what don’t you share with your children? What are the boundaries?

CT: There’s a fine line between providing a backstop and creating entitlement. What are the keys to instilling personal humility and avoiding entitlement?

MC: Ultimately our children never had failure. If worse came to worse, we got them the resources they needed. Teaching kids resilience and overcoming things in life is important. Kids do need failure in their lives, but which things to let them fail? The way we parent today is so different from 30 years ago. I’m much more involved in their lives. My 30-year old still calls me and asks my advice on issues. You can’t parent the way your parents did. One thing I’ve learned—when your children are happy where they are, leave them where they are. Keep the communication open. Parenting is so complex that you can replicate some mistakes even when you’re telling yourself not to!

CT: Helicopter parents—help or hurt?

MC: For me, it helps more because it affirms who I am—a parent. Parenting became a real something for me. But now, it’s one thing to “helicopter,” and another thing to intervene, to have “boots on the ground.” That’s not good for the kid, the parent or the administration [of a school or college]. But a helicopter is better than what my father was like, and I want this involvement in my child’s life. That’s part of my legacy, and I love that.

Editor’s note: A prominent theme in Craig’s observations and in Tolleson’s questions and responses was the need to adapt a family’s patterns to changes in larger society. Craig’s description of the difference in the way he was himself parented and the way his parenting has changed among his three children is a good example. Another theme was the importance of effective communication with appropriate transparency within the family. Both Craig and Tolleson struggled with describing the “right” vulnerabilities and failures to share with children versus the ones that might alarm children or invade one’s own privacy—and both agreed that transparent, supportive communication is key to a successful family.

You can read part 2 of the interview here.